Your podcast discovery platform

Curious minds select the most fascinating podcasts from around the world. Discover hand-piqd audio recommendations on your favorite topics.

piqer for: Global finds Technology and society Globalization and politics

Elvia Wilk is a writer and editor living in New York and Berlin, covering art, architecture, urbanism, and technology. She contributes to publications like Frieze, Artforum, e-flux, die Zeit, the Architectural Review, and Metropolis. She's currently a contributing editor at e-flux Journal and Rhizome.

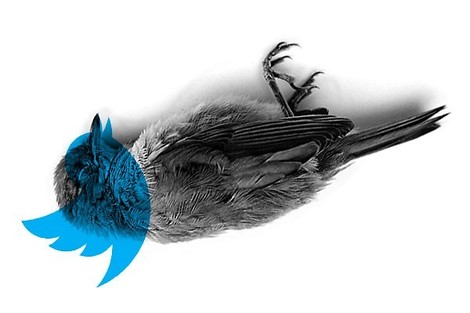

What Should Twitter Do?

One man’s troll farm is another man’s room of old friends. Or at least Twitter was full of friends, and fun, for Mike Monteiro, until he had to admit it had become partially, and then very, unpleasant.

In this personal history of the medium, Monteiro describes his first years on Twitter using it for jokes—and also for meeting people, interacting remotely, and even learning to express himself better in writing. He also believed it to be a platform for political discussion that could play an active part in the way people related to each other across space and culture.

“In 2008 I thought Twitter helped elect a president. I was off by eight years.”

As we have seen by now, Twitter’s free-speech platform has become riddled with hate speech, including but not limited to the accounts of the president of the USA. The company's business goals—staying afloat—are in sharp contrast with a presumed ethical obligation to monitor abuse. What happens on Twitter should stay on Twitter, but increasingly it has (negative) effects far beyond the browser window.

“This isn’t about Twitter anymore. This is about something bigger. When Donald Trump tweets us into war, the bombs don’t fall inside Twitter. When Donald Trump tweets us out of the social contract, citizens who’ve never used the service are left to suffer.”

Given the far-reaching consequences of a tweet, what is Twitter's responsibility toward its users? What is ours?