Your podcast discovery platform

Curious minds select the most fascinating podcasts from around the world. Discover hand-piqd audio recommendations on your favorite topics.

piqer for: Global finds Technology and society Health and Sanity

Nechama Brodie is a South African journalist and researcher. She is the author of six books, including two critically acclaimed urban histories of Johannesburg and Cape Town. She works as the head of training and research at TRI Facts, part of independent fact-checking organisation Africa Check, and is completing a PhD in data methodology and media studies at the University of the Witwatersrand.

Grave Robbers & Genocide: The Namibian Skeletons In The American Museum Of Natural History

A mere half-century or so ago, it was still de rigueur for anthropologists and archaeologists to steal what they could not otherwise obtain by legal means. Even sanctioned acquisitions were often suspect (see, for example, the older case of the Elgin marbles, stolen from Greece and sitting in a British museum).

In Africa, in the Americas, and in Asia, this practice often extended to burial chambers and body parts—institutionalized grave-robbing, itself an extension of a racist system that had determined black and brown bodies to be specimens rather than humans. Examples of this include horrors like the story of Khoekhoe woman Sarah Baartman whose brain, sexual organs and skeleton (the latter obtained after her death by boiling the remaining flesh from her body) were displayed in a museum in Paris until the 1970s, and only repatriated in the early 2000s.

The truth is, almost every major and even many minor natural history or ethnographic museums today still hold human remains of dubious origins.

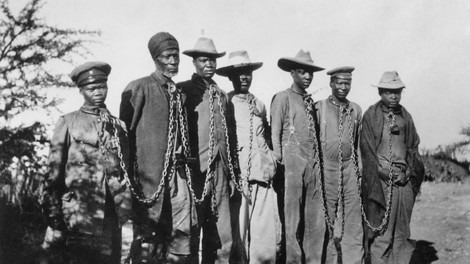

In late 2017, attention turned to a handful of boxes held by the American Museum of Natural History in Manhattan—boxes that contained human skulls and skeletons stolen from Africa by European colonists, later paid for by an Austrian bone collector named Felix von Luschan. These remains were collected in the early 1900s during the German-initiated genocide of the Herero and Nama populations living in what would become Namibia. More than 65,000 Herero and 10,000 Nama were killed. Their descendants are involved in a lawsuit, and are asking the courts to find Germany financially and legally responsible for the act.

Museums, though, still appear reluctant to acknowledge their failure of ethics in the continued study of such ill-gotten remains. This reticence has, in turn, spawned a generation of activists who travel the world helping people to locate and repatriate the stolen bodies of their ancestors.

As for the fate of the bones in the American museum, time will tell.