Your podcast discovery platform

Curious minds select the most fascinating podcasts from around the world. Discover hand-piqd audio recommendations on your favorite topics.

piqer for: Boom and bust Global finds

German economist with a sense of humor, not just relative to accountants. Chief economist at the London-based Centre for European Reform (CER), recently brexited to Berlin. Former fellow at The Economist, economics PhD at Stockholm University in Sweden. Christian covers European economics and integration and has, as a former Londoner, a pathological interest in the economics of real estate.

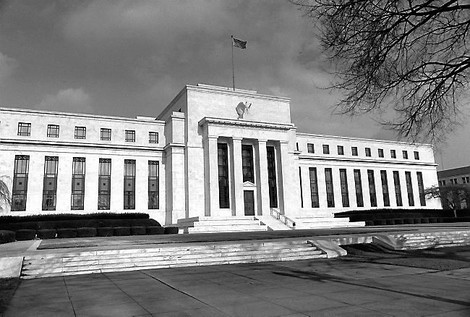

Is It Time To Rethink Monetary Policy?

This is a great essay on an admittedly complex topic: monetary policy. Ryan Avent (The Economist) looks at the failures of monetary policy, going all the way back to the Great Depression but also looking at the aftermath of the Great Financial Crisis of 2008/09, during which monetary policy has failed. What is needed is a regime change, something that shocks the economy onto a better path of optimism and faster growth.

But how to deliver such a regime shift? Here is the key paragraph (emphasis mine):

Taking a step back, central bankers see themselves as technocrats, there to tend the monetary machinery. They can change the oil and top up the tanks, but are not constitutionally disposed to swapping out the engine. Historically, when monetary “regime change” has occurred—when the public has been jolted out of a bad equilibrium into a good one—it is as a result of a political shift. It was Roosevelt that delivered regime change—by suspending gold convertibility—not the Federal Reserve. It was Richard Nixon who ended America’s role in the international gold standard set up after the second world war ... [and it was] a political commitment to Paul Volcker by Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan that facilitated the end of high inflation in America. In Japan, where nominal GDP is at last rising in sustained fashion, it was the election of Shinzo Abe, who essentially ran on a platform of monetary regime change (and nationalism), that made the difference. Monetary policy is powerful. But independent central banks lack the institutional capacity to force a regime change. Historically, it has taken politicians with popular mandates to do that. Whatever one’s theory of Fed failure in the Great Recession—monetary timidity, monetary impotence, or secular stagnation—the solution necessarily entails decisive political action.

I tend to agree with him, and in the US we may see a political shift towards a different sort of macroeconomic policy. I have no such hope for Europe, though.