Your podcast discovery platform

Curious minds select the most fascinating podcasts from around the world. Discover hand-piqd audio recommendations on your favorite topics.

piqer for: Global finds Technology and society Globalization and politics

Elvia Wilk is a writer and editor living in New York and Berlin, covering art, architecture, urbanism, and technology. She contributes to publications like Frieze, Artforum, e-flux, die Zeit, the Architectural Review, and Metropolis. She's currently a contributing editor at e-flux Journal and Rhizome.

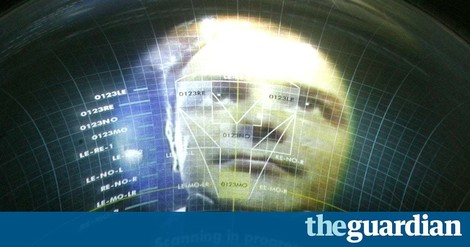

AI Determines Sexual Orientation Just From Looking At A Face

What good would AI be if it could only recognize your face? No—to be useful (and nefarious), AI has to be interpretive. And much of the current development in machine intelligence is about building machines that can interpret human faces better than humans can.

And it's not only about interpreting your expression at a given point, or genetic factors like your age or your race: machines are learning how to detect traits that we have long thought not to be biologically determinate, but which can apparently be extrapolated over large populatioins. Like political leaning. Like sexual orientation.

Kosinski’s “gaydar” AI, an algorithm used online dating photos to create a program that could correctly identify sexual orientation 91% of the time with men and 83% with women, just by reviewing a handful of photos.

Yet all machines are human creations, and as such they are built with human biases. Much of how AI interprets a face depends on the data set it’s been given in order to learn—and those data sets inevitably reflect the biases and inclinations of the researcher. This raises questions not only about how it learns, but about what its conclusions might be used for.

“You’re going down a very slippery slope,” said one computer science professor in regards to new facial recognition software. Imagine an algorithm is wrong about someone's sexual orientation just one time in a thousand—that might amount to one hate crime driven by its mistake.